Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

Today we’re looking at “Black Man With a Horn,” a T. E. D. Klein story first published in Arkham House’s New Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos in 1980, and anthologized several times since.

Spoilers ahead.

“There is something inherently comforting about the first-person past tense. It conjures up visions of some deskbound narrator puffing contemplatively up a pipe amid the safety of his study, lost in the tranquil recollection, seasoned but essentially unscathed by whatever experience he’s about to relate.”

Summary

Though his natural habitat is New York City, nameless narrator writes from a shabby bungalow in Florida. It should be reassuring that he writes in first person, right? Doesn’t it imply he’s lived through the ordeal? Alas, his part in another man’s horror story isn’t over yet. Howard would have understood this sense that both his life and death matter little.

Yes, that Howard. Narrator was Lovecraft’s friend and a “young disciple.” His early work received praise, but now he feels eclipsed by his long-dead mentor. We open as he returns from a conference that’s only increased his literary anhedonia. His flight is a tragicomedy of pratfalls; he winds up seated beside a big, false-bearded man who almost knocked him down earlier. The man wakes to stare at him with momentary terror, but narrator’s not the sight Ambrose Mortimer, former missionary, dreads. Mortimer has left his post in Malaysia, fearful that he’s being followed. His work went fine until he was sent to minister to the “Chauchas,” seeming primitives who still speak agon di-gatuan, the Old Tongue. They kidnapped Mortimer’s colleague, in whom they “grew something.” Mortimer escaped but has since heard a Chaucha song, the singer mockingly out of sight.

Mortimer’s on his way to Miami for R & R. Narrator shares the address of his sister Maude, who lives nearby.

Later, narrator spots Mortimer in the airport, flipping through gift store LPs. One cover makes him gasp and run — unaccountably, it shows John Coltrane and sax, silhouetted against a tropical sunset, just another black man with a horn.

In the NYC Howard fled, narrator’s made a “good life amid the shade,” but he fears his friend would have been even more appalled by the modern city, where dark skin crowds out white, salsa music blares, and one can walk the length of Central Park without hearing English spoken. At the Natural History Museum with his nephew, narrator sees another black man with a horn. This one is embroidered on a ceremonial robe from Malaysia: a figure with a pendulous horn in its mouth that sends smaller figures fleeing in panic. It’s supposedly the Herald of Death, and the robe’s probably Tcho-Tcho in origin.

Tcho-Tcho? Lovecraft’s “wholly abominable” race? Maybe Mortimer mispronounced their name “Chaucha.” Speaking of Mortimer, he befriended Maude, then disappeared. Police are looking for a Malaysian man, known to have stayed in the Miami area. Narrator recognizes the suspect as a man he saw on the plane.

Narrator’s amateur sleuthing unearths the legend of the shugoran (elephant-trunk man), a demon used to frighten Malaysian children. It sounds like the figure on the Tcho-Tcho robe, but its horn is no instrument. It’s part of its body, and doesn’t blow music out, but sucks in instead.

Maude tells narrator about another neighborhood disappearance — a restaurant worker who vanished from a dock. The boy’s found dead with his lungs in throat and mouth, inside out. On a visit to Maude, narrator visits the motel where the Malaysian stayed. Later he learns that a maid glimpsed a naked black child, supposedly the man’s own, in his room.

Someone vandalizes Maude’s house, trampling under her window and leaving roof-to-ground slashes in the siding. She moves farther inland.

Narrator visits Florida again, to settle the deceased Maude’s affairs. Strange inertia keeps him in her bungalow. There’ve been more acts of vandalism, even attacks by an unidentified prowler. The latest was right next door. His neighbor saw a big black man in her window. He wore what looked like a gas mask or scuba gear, and left swim-fin-like footprints.

Narrator wonders if the prowler was looking for him. Whether it will return to make for him a horror writer’s proper end. Howard, he asks, how long before it’s my turn to see the black face pressed to my window?

What’s Cyclopean: No two sources manage to transliterate “Tcho-Tcho” the exact same way. No doubt some dark conspiracy underlies this lexical incongruity.

The Degenerate Dutch: The narrator of “Black Man” is hyper-aware of race, and finds all races alarming in their own unique ways—very much including anglos. No savior civilization here.

Mythos Making: You were just waiting to find out why the abominable Tcho-Tcho were so abominable, weren’t you?

Libronomicon: These days, “books with titles like The Encyclopaedia of Ancient and Forbidden Knowledge are remaindered at every discount store.” And in this story, much like the actual 1980s, dark hints of dread and inhuman truth are more likely to appear in the newspaper than the book store.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Everyone in this story appears pretty sane, if sometimes awfully fatalistic.

Anne’s Commentary

Let’s start with full disclosure: I love love love T. E. D. Klein. I wish I could say a spell to relieve him of his long writer’s block in the same way I wish I could use Joseph Curwen’s method to resurrect Jane Austen. I want more stories, more novels, epic series that would make Brandon Sanderson blanch! But alas, to paraphrase Gaiman, Mr. Klein is not my bitch, and I’ve yet to perfect the Curwen method. Soon, soon….

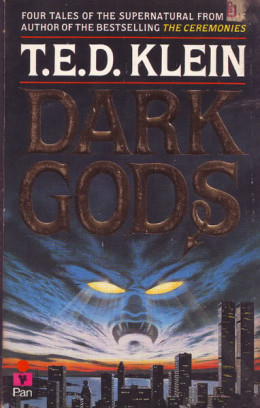

I couldn’t choose a favorite from Klein’s great novella collection, Dark Gods, and I hope we’ll read more of them. “Black Man with a Horn” is the most Lovecraftian of them, to use the adjective that our narrator says confirmed HPL’s literary immortality. I mean, what could be more Lovecraftian than a story about a Lovecraftian writer and one of Lovecraft’s own circle? In the great one’s tradition, Klein’s narrator even goes unnamed, a choice that underlines his sense of fading into Howard’s long shadow. Why, conference planners can’t even get narrator’s most famous book right, printing its title in the program as Beyond the Garve. There’s a sic to sicken, poor guy, and a detail right to the nth degree.

And detail is the thing about Klein’s work. For once in my critical life, I’m going to descend to that favorite term of New York Times reviewers and proclaim Klein SFF’s master of the quotidian! He recreates the everyday and commonplace with a vividness that makes any encroaching weird all the darker, all the more terrifying. Most of us don’t live in crumbling castles or haunted mansions, after all. We don’t frequent primordial ruins or clamber through endless undergrounds. However, we do fly on airplanes. We do go on vacation to Florida, perhaps to visit snowbird relatives in bungalows. Sure, the Natural History Museum can be scary — see Preston and Child at their eeriest — but it’s part of any tourist’s itinerary, the stuff of innumerable schoolkid memories. Hey, even Malaysia’s a fairly ordinary place, once you get used to the humidity and invasive plants. The people are friendly, the scenery splendid. That is, until you venture too far into the interior, where the Chaucha/Tcho-Tcho live. And even they seem quotidian, all smiling and agreeable. On the outside.

It’s a front, though. A mask. A trap. These are people who will GROW THINGS INSIDE YOU, and you’ll DIE of it, probably gratefully. They’ll also grow things in treacle inside black hatboxes, and said things will later peer at the maid from the bathroom, then flounder off into a convenient canal to SUCK VICTIMS’ LUNGS OUT THEIR THROATS. They look in windows, too, all black and snouty. Things that look in windows, at night, silent and hungry, they are bad. They are one of the beating hearts of terror, especially when the window in question is a picture window in a tacky bungalow in a tacky suburban development.

Weird shit among us normal folk! In Howard’s quaint New England, in King’s small-town Maine, in Klein’s Florida and NYC! The more you can make us feel at home, the higher you can make us jump when that black face presses against the window glass.

Which brings me to the blackness of the face. Klein and race, Klein and the other. What’s going on with this aspect of his web-intricate fiction? Black and brown and yellow people often unnerve Klein’s white characters. It’s in “Children of the Kingdom” that he most closely examines the dynamics of racial/alien fear, but the theme is also prominent in “Black Man with a Horn.” Lovecraftian narrator stumbles over “some Chinaman’s” lunch and gets icky sauce on his pant cuffs. Said Chinaman is a “bloated little Charlie Chan.” A black plane passenger glares at narrator when narrator reclines his seat. Said black passenger also wails like a banshee when he burns himself with a cigarette, petrifying Mortimer and narrator. Mortimer is scared by a picture of John Coltrane and his sax. At the Natural History Museum, Puerto Rican boys worship a Masai warrior, a black woman fails to restrain her children, and a black youth shadows innocent Nordic tourists, grinning mockingly. In NYC in general, Howard’s foreign hordes have gained ground, dark faces overwhelming the pale ones. Mortimer notes that the Chauchas seem to have a touch of black in their Asiatic. A black porter “towers” over Maude at the Florida airport. The Malaysian Djaktu-tchow is suspected of harboring a naked black child. The shugoran itself is “as black as a Hottentot.” It’s the black man with a horn, the black Herald of Death, the black face in the window. Black!

Yet when narrator’s niece scolds him about staying on Manhattan’s West Side, where “those people” are so prevalent, narrator shrugs her off. He claims he stays because he grew up there, knows where the cheap restaurants are. To himself he admits that he’s actually choosing between the whites whom he despises and the blacks whom he fears. Somehow he “preferred the fear.”

Huh. Now that’s an interesting statement. To fear the other and alien, and yet to prefer that fear to the normal, the known, the like-me. Is this what makes someone like our narrator write horror and fantasy, rather than “realistic” fiction? Is this what makes him stay on in a house that may be the very definition of dull normal, but which also has a window to which a black face may finally press?

Not the Herald of Death. Death itself, come to steal one’s breath in the most direct and gory manner possible.

Curious, curious, curious, the darkening dance of repulsion and attraction in this story. No wonder I keep coming back to it, nervous but eager.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

T. E. D. Klein has won widespread acclaim for his limited output, and “Black Man With a Horn” is a recognized classic of cosmic horror. So it will do no harm to admit that I personally appreciate this story more on an intellectual than an emotional level. It’s extraordinarily clever thematically, meta as hell, and implies a lot of horror through extremely limited detail… and I find myself too busy unpacking the meta to be even slightly creeped out.

It really is clever, though. We authors are often enjoined against writing stories about authors. Here the conceit works: the narrator’s a Mythosian writer less out of a need for self-insertion, and more to comment on both “my old friend Howard” and the subgenre he defined. Narrator complains that he’s described solely as “Lovecraftian,” his accomplishments effaced behind the label. But the whole story revolves around the question of what it really means for an author, and a story, to be “Lovecraftian.”

Race, Klein recognizes full well, is central to that question. Even while calling New York’s immigration-based hellishness a product of Howard’s own fevered fears, the narrator shows himself obsessed with, and hyper-aware of, race. He mentions the perceived ethnicity of every person he encounters, frequently in judgmental fashion. Though he doesn’t share HP’s phobias, he admits to fearing black people and despising white people. (He never mentions his own race—given Klein’s I spent a lot of time distracted by the question of whether he was Jewish, or white himself. It would put a different read on his judginess, either way.) Racial fears blend into cosmic, with the Tcho-Tcho as prototypical Scary Foreigners Who Worship Elder Gods And Are AFTER YOU. That seems as good a definition of “Lovecraftian,” as a specific subset of cosmic horror, as one might ask for.

But does the story itself actually buy into the narrator’s fears and stereotypes? Every mention of race is thoroughly self-aware and metatextual, and yet the Tcho-Tcho really are scary brown people. Then there’s that weird moment with the “capering” African American boy following the family of white tourists. The titular Black Man seems a deliberately ambiguous figure, who can be seen both as black in the ordinary racial sense (a la the existential terror of John Coltrane), and as a supernatural figure who just might be Nyarlathotep’s avatar. I wander through this story littering the e-book file behind me with a trail of “Ummmm” comments and raised eyebrow emojis. Following this trail, I eventually tracked my discomfort: for all “Black Man” tries to say something insightful about Lovecraft’s treatment of race, all the characters of races other than the narrator’s (whatever that may be) are presented as archetypal symbols of horror rather than as actual people.

The story is also “Lovecraftian” in that both it and the narrator continue a correspondence with Lovecraft throughout. A quote from one of the master’s letters sets off each section, and the story itself is framed as a letter in return, addressed to “Howard.” This is narratorial genre-savviness above and beyond “I just happen to have read the Necronomicon and memorized a relevant passage.” And indeed, “Lovecraftian” writers are more likely to be in conversation with their genre’s namesake, addressing him by name or otherwise, than people working in the tradition of many other golden age writers. (How many stories are explicitly in conversation with Burroughs or Asimov? Their tropes, techniques, and assumptions have been thoroughly assimilated into genre, and the arguments in which they were prominent continue, but the resulting narratives are rarely quite so personal. There are still stories about AI ethics, all owing a debt to the Three Laws, but there’s no Neo-Asimovian subgenre.)(I’m not entirely confident in that last parenthetical, but leave it in hoping that I’m at least interestingly wrong.)

Nor are Lovecraft’s stories the only source for the narrator’s genre-awareness. He compares his situation to cozy mysteries, and to epistolary Victorians. None of this helps—if anything, he seems to draw a greater sense of helpless fatalism from both. This too, is Lovecraftian. Knowing more almost never helps you get away from the scary thing—it just gives you a better view of what’s coming. Klein’s narrator, informed not only by the Miskatonic library, but by newspapers, correspondents, and whatever can be found at the discount store, is quite well set up to correlate their contents—and to assure us, like an earlier narrator, that the ability to do so is no mercy.

Next week, we jump back into the public domain, and into one of Lovecraft’s best-known inspirations, with Poe’s “Fall of the House of Usher.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.